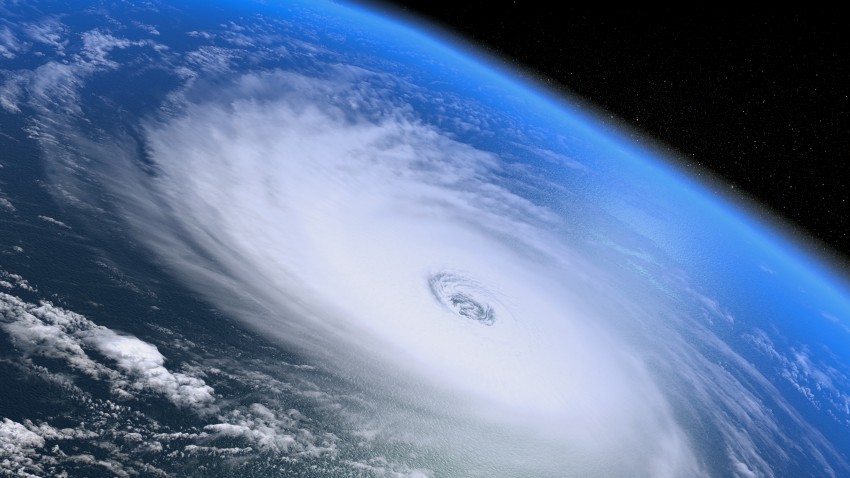

On the heels of the tenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina’s devastating landfall along the Central Gulf of Mexico, on Monday, August 31st, we recorded a first in the hundred-or-so year history of reliable tropical cyclone tracking: three major hurricanes moving simultaneously across the Pacific. Fortunately this awe-inspiring moment was of mostly academic interest since none of the three storms posed a significant threat to any populated land masses, but it was certainly an intimidating sight on satellite imagery. Couple that with Fred becoming the first hurricane to move through the Cape Verde Islands in the far eastern Atlantic since 1892, and it might be tempting to look for a larger causal force behind a perceived growing tropical cyclone threat, such as everybody’s favorite climatic boogeyman, man-made global warming. However, there’s actually a much more direct correlation between cycles of hurricane frequency, especially in the Eastern Pacific and Atlantic tropical basins, and the warm phase of the ENSO (El Nino Southern Oscillation).

Read full article

![]()