Major Gulf of Carpentaria Cyclone Nora This Weekend!

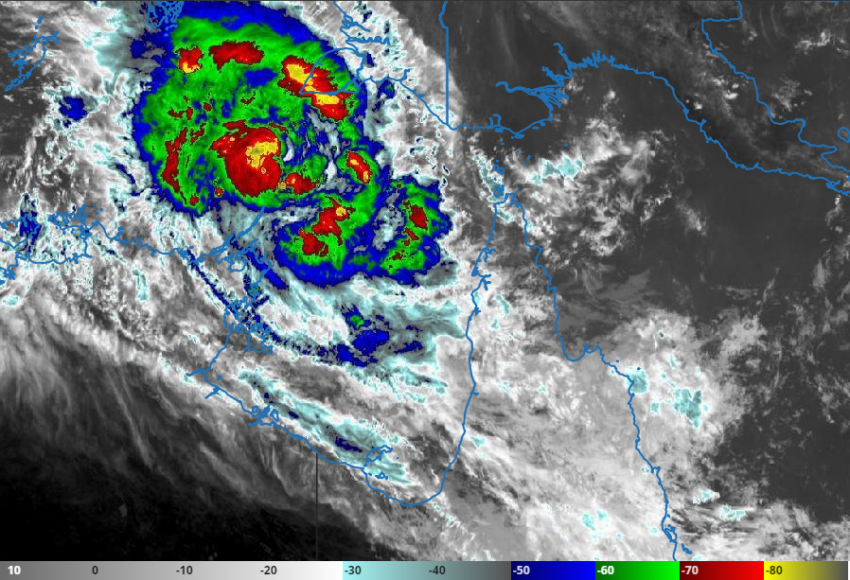

Tropical Cyclone Nora is gaining strength over the Arafura Sea (see satellite image above, courtesy of Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology). Winds and rains are already increasing over Marchinbar Island. Model guidance indicates the cyclone will turn southeast into the very warm waters of the Gulf of Carpentaria. It’s a favorable environment for intensification and interests all along the Gulf coast should pay close attention!

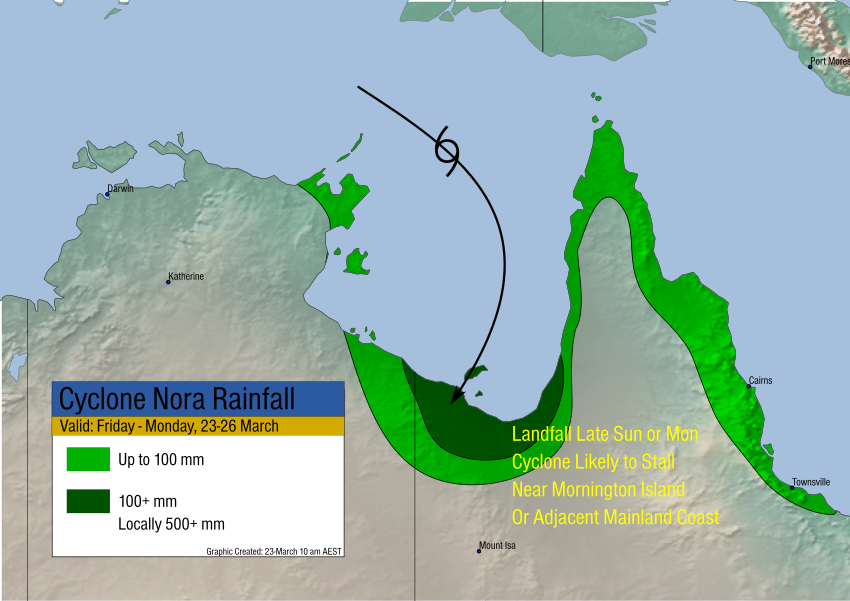

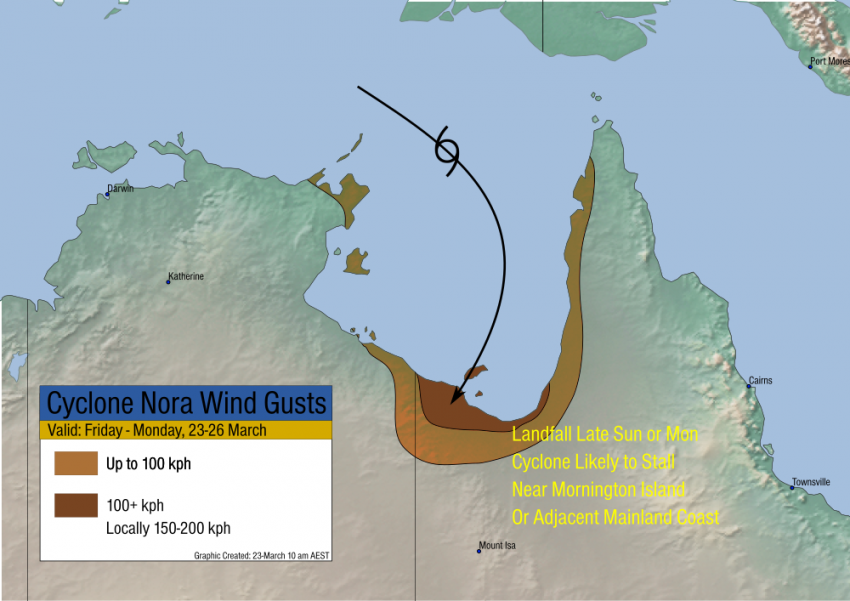

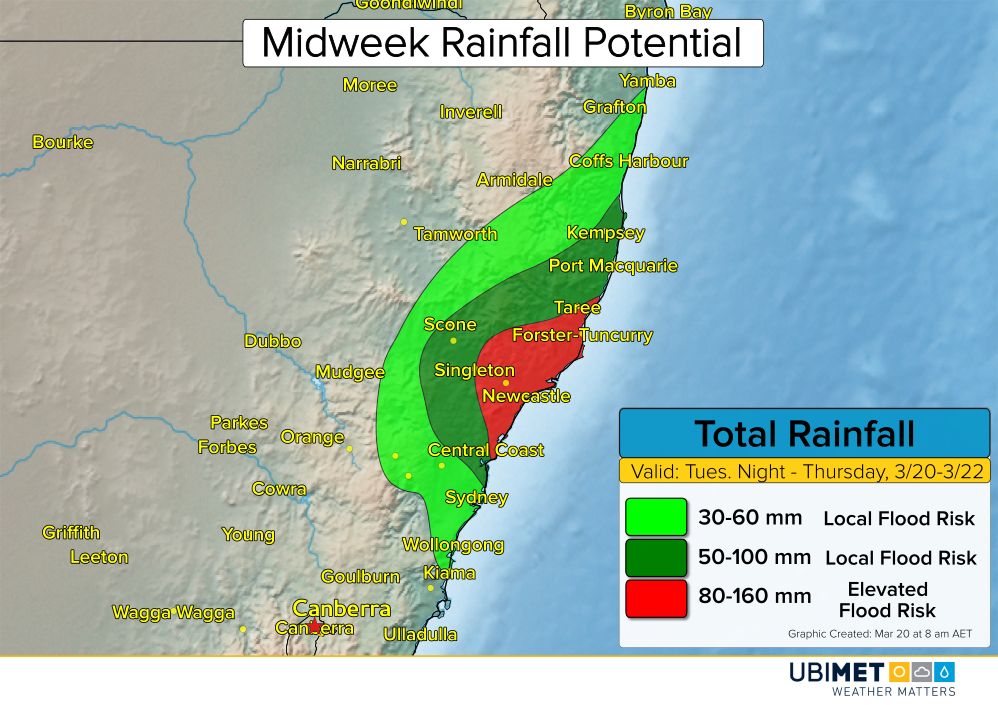

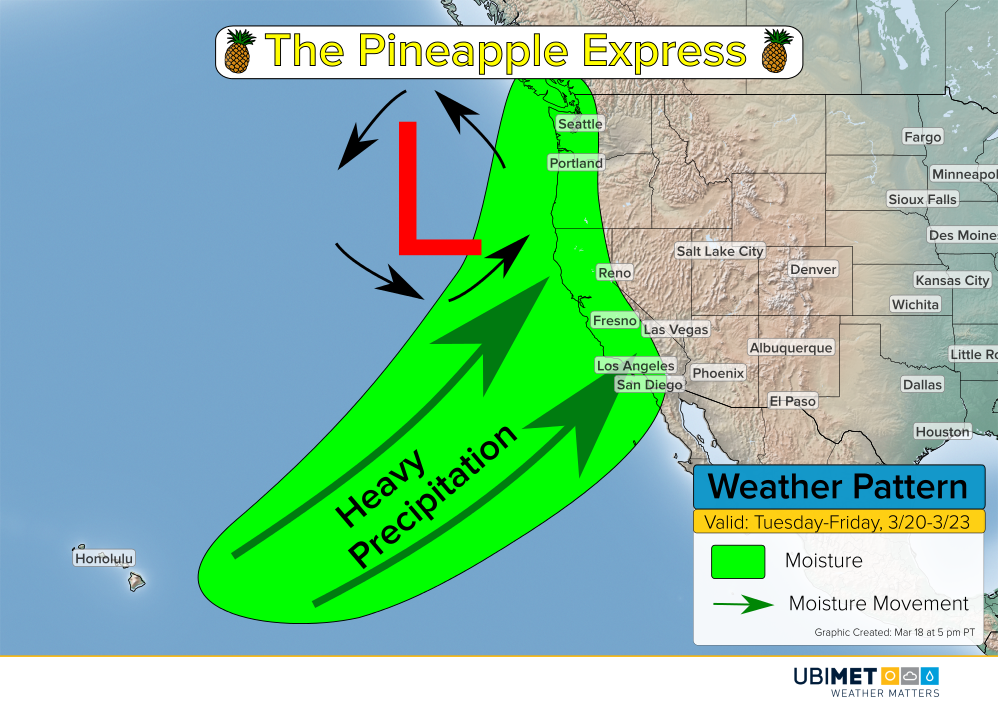

Nora will likely be a small but severe cyclone as it approaches Mornington Island or the adjacent mainland late Sunday or Monday. The heaviest impacts will fall on this region, including northern QLD and northeastern NT. Destructive wind gusts of 200 mph are possible along with torrential rains up to 500 mm (see graphics below)! A moderate storm surge could exacerbate flooding issues in this area. We’ll continue to monitor this dangerous situation and issue further updates in the coming days.