Wet and Windy Weather Coming for Perth Early Next Week!

It’s been a typically active early winter in southwestern Western Australia. During the month of June, Perth has seen about 120 mm of rain, close to the climatological normal there. However, in the hills nearby, the Bickley station has seen more than 205 mm in June. Model guidance suggests the month of July will start with another storm rolling in from the Indian Ocean.

The storm will approach the southwest coast late on Sunday with the Capes seeing increasing winds late in the day. Winds and heavy rains will spread across much of the southwest, including the Perth metro, through the day on Monday. A second windy period could affect the region on Tuesday morning. The heaviest rains are expected in Perth on Monday afternoon and evening, when there could be some lightning. Strong storms with gusty winds and small hail could occur in this time frame.

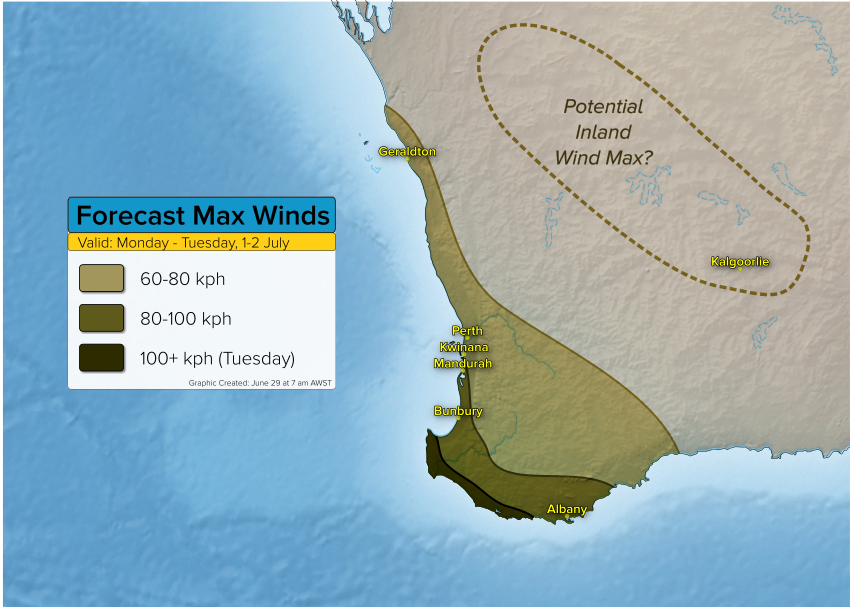

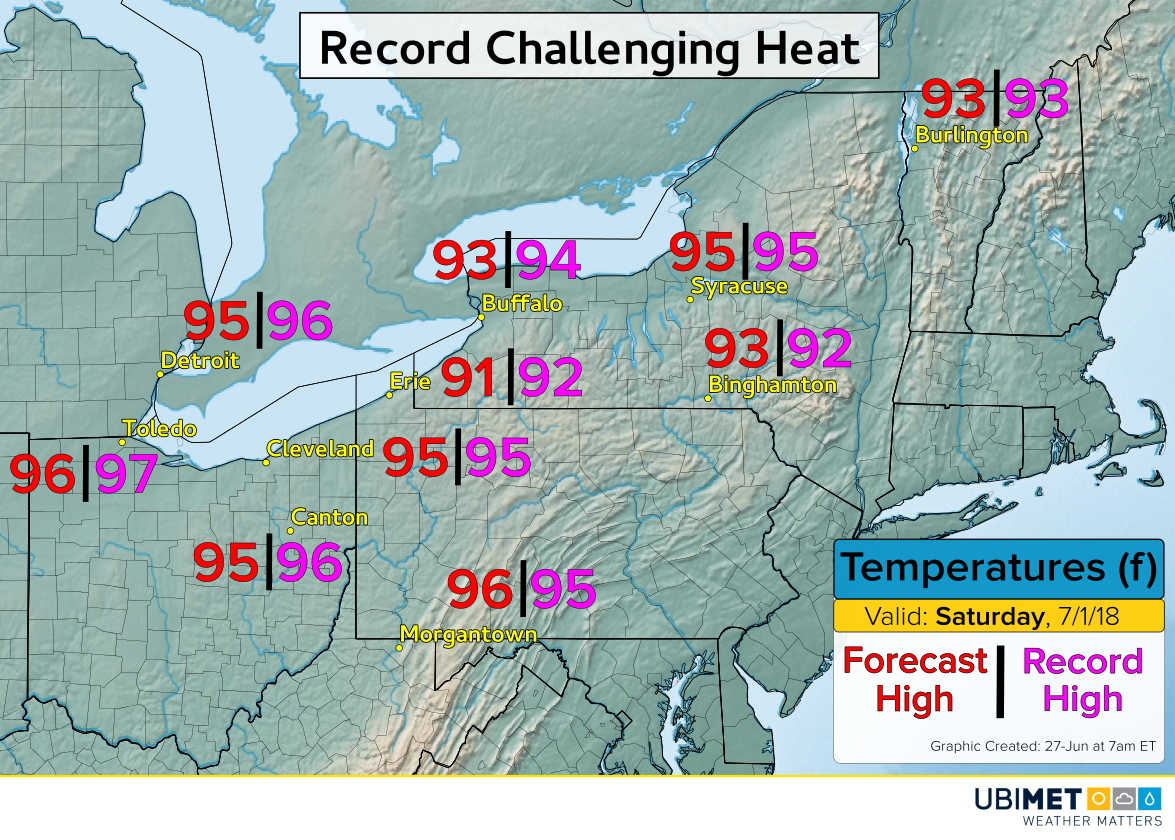

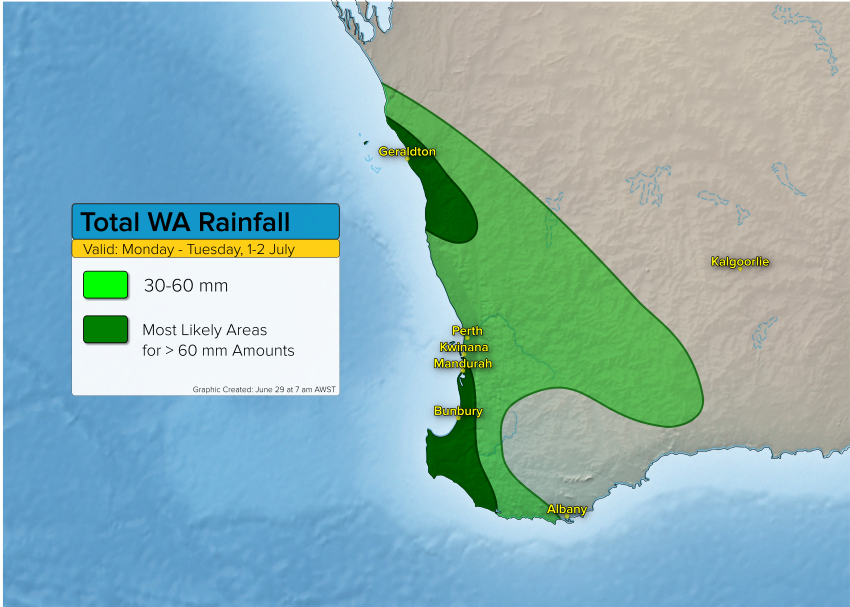

Total rainfall amounts of 30-60 mm will be widespread across the region (see graphic above). At this time, it appears that rainfall amounts exceeding 60 mm are most likely south and north of Perth, but we can’t rule out heavier rains in Perth. The strongest winds as usual will affect the Capes with gusts exceeding 100 kph (see below). Perth will see gusts occasionally in the 60-80 kph range, strongest near the immediate coast. There may be an area of high winds up to 80 kph over inland areas as indicated by the dotted line, although model guidance is split on this possibility. Lead photo courtesy flickr contributor abstrkt.ch