Rain and Snow for the Pac Northwest

Active weather is going to continue into the early part of the week for the Pac Northwest. Heavy snow will fall in higher elevations with rain and even some snow in the lower elevations.

Active weather is going to continue into the early part of the week for the Pac Northwest. Heavy snow will fall in higher elevations with rain and even some snow in the lower elevations.

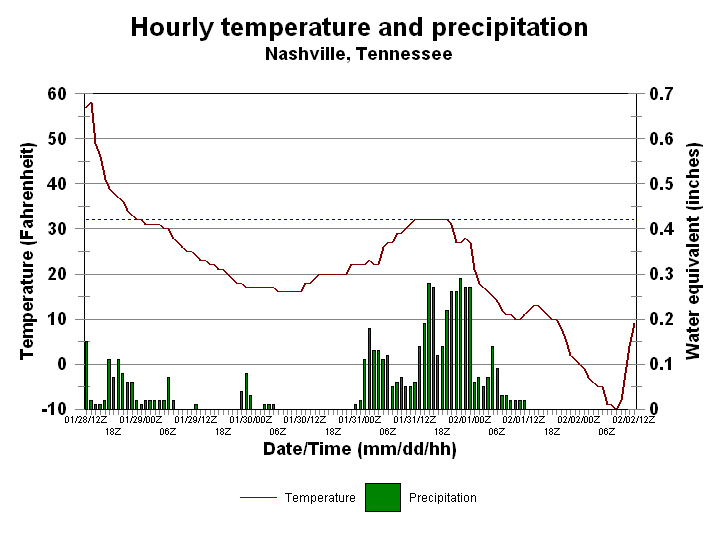

The morning of Sunday, January 28 in 1951 broke unusually mild across the Mid-South. In Nashville, Tennessee, temperatures were nearly 60 degrees despite cloud cover and periodic rain. However, an Arctic front surged through the region, dropping temps into the mid-30s by early afternoon. By that evening, temperatures were at freezing and still dropping. Rain began to freeze on trees and power lines, the beginning of one of the worst ice storms ever to strike the U.S.

The Arctic air mass, shallow but extremely cold, became locked in place thanks to stationary high pressure over the Plains. Meanwhile, waves of low pressure rode northeast out of northern Mexico, drawing rich Gulf moisture up and over the frigid surface layer. Periods of freezing rain, sleet, and snow, heavy at times, plagued the region for the next three days. Significant icing was reported all the way from Texas and Louisiana to Pennsylvania. However, the hardest hit area was between Memphis and Nashville, Tennessee up to Lexington, Kentucky.

Nashville saw 3.83” of liquid meltwater equivalent on January 31 alone, still the all-time record for single day precipitation. Up to four inches of solid ice (freezing rain and sleet) accumulated on roads, bridges, roofs, trees, and power lines. Several inches of snow fell to finish the storm on February 1, adding to the misery. The storm was followed by staggering cold. Both Memphis (minus 11) and Nashville (minus 13) either tied or set all-time record low temperatures early on February 2.

Although it came to be commonly known as the “Great Blizzard of ’51”, it was in reality the heavy icing, not high winds and blowing snow, that was the really disruptive factor. The storm caused a total shutdown of transportation in the Nashville area for two days. Power and telephone outages were widespread and lasted upwards of a week in many cases, leading to a bewildering sense of frontier isolation for many residents.

Some Nashville residents compared the frequent, vivid failure of powerlines and transformers to a fireworks show. Others likened the accumulation of snow and ice on streets, blown and drifted by bitter northerly winds, to frozen ocean waves. One man, taking a break from storm clean-up, warmed himself by a portable indoor heater, only to walk back outside and see the buttons on his overcoat shatter due to the sudden freeze. The storm cost 25 lives and caused 500 more injuries. The final price tag of $100 million, or nearly $1 billion in 2017 dollars.

Fortunately, in 1951 many homes still possessed alternative means of heating like wood stoves and fireplaces. Likewise the dependence on communications and transportation was much less then compared to now. How much more disruptive might a storm of the same magnitude be today?

A clipper system responsible for snowy conditions Monday will continue east Tuesday into Wednesday.

During the evening of January 28th, 1922, movie fans settled into Washington, DC’s largest theater, the Knickerbocker, to enjoy the silent comedy “Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford”. Perhaps as many as a thousand people were packed into the new theater, eager to relax and enjoy the show.

They deserved the break after struggling all day with the heaviest snowstorm on record in the nation’s capital. Well over two feet had fallen across the city. Rock Creek Park, on the north side, had measured 33 inches with over three inches of meltwater equivalence. It was all thanks to slow-moving cyclone that followed a classic track for blockbuster snowstorms in the Mid-Atlantic. Low pressure developed in the Gulf of Mexico on 27-Jan, then exploded off the southeast coast, drawing energy from the warm Gulf Stream. High pressure over New England sealed the storm off from faster jet stream steering winds. This allowed the system to drift slowly and dump heavy snows along the Eastern Seaboard for most of three days. Railroad lines were paralyzed and although Congress was forced to adjourn early, the congressmen were stuck in the city, including Andrew Jackson Barchfield of Pennsylvania. Unlike contemporary storms, this one hit with little to no advance warning. Indeed, the weather forecast from the day before predicted fair skies with rising temperatures. Fortunately, the storm struck late on Friday into a weekend, somewhat reducing the disruption to normal business.

Just after intermission, around 9 p.m. that Saturday night, the roof of the Knickerbocker collapsed. Survivors and passers-by outside almost immediately began to try to rescue those trapped by the rubble. The army was called in to assist with rescue operations and maintain control of the scene. Despite their heroic efforts, 98 people lost their lives in the disaster, including the Pennsylvanian Rep. Barchfield, along with a former U.S. senator and several business leaders. An additional 133 were injured.

In the aftermath of the disaster, officials investigating the causes had to sift through several theories. One of the more interesting was that the structure had been weakened by specific notes sounded by the pipe organ that sometimes accompanied movie screenings. Faulty design eventually received the official blame. Specifically, the flat roof and use of arch girders instead of more robust stone pillars allowed for the structure to be overwhelmed by the weight of tons of wet snow. This judgment may have allowed the death toll of the tragedy to rise to an even 100, but only years later – both the architect and owner of the theater committed suicide in 1927 and 1937, respectively.