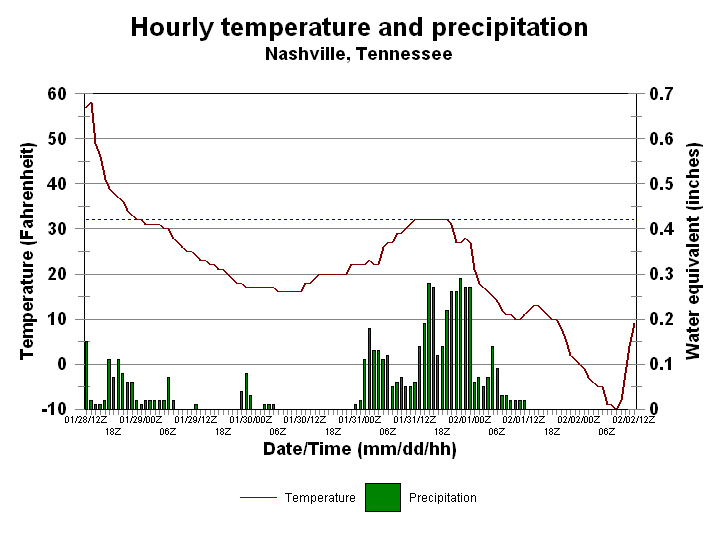

The morning of Sunday, January 28 in 1951 broke unusually mild across the Mid-South. In Nashville, Tennessee, temperatures were nearly 60 degrees despite cloud cover and periodic rain. However, an Arctic front surged through the region, dropping temps into the mid-30s by early afternoon. By that evening, temperatures were at freezing and still dropping. Rain began to freeze on trees and power lines, the beginning of one of the worst ice storms ever to strike the U.S.

The Arctic air mass, shallow but extremely cold, became locked in place thanks to stationary high pressure over the Plains. Meanwhile, waves of low pressure rode northeast out of northern Mexico, drawing rich Gulf moisture up and over the frigid surface layer. Periods of freezing rain, sleet, and snow, heavy at times, plagued the region for the next three days. Significant icing was reported all the way from Texas and Louisiana to Pennsylvania. However, the hardest hit area was between Memphis and Nashville, Tennessee up to Lexington, Kentucky.

Nashville saw 3.83” of liquid meltwater equivalent on January 31 alone, still the all-time record for single day precipitation. Up to four inches of solid ice (freezing rain and sleet) accumulated on roads, bridges, roofs, trees, and power lines. Several inches of snow fell to finish the storm on February 1, adding to the misery. The storm was followed by staggering cold. Both Memphis (minus 11) and Nashville (minus 13) either tied or set all-time record low temperatures early on February 2.

Although it came to be commonly known as the “Great Blizzard of ’51”, it was in reality the heavy icing, not high winds and blowing snow, that was the really disruptive factor. The storm caused a total shutdown of transportation in the Nashville area for two days. Power and telephone outages were widespread and lasted upwards of a week in many cases, leading to a bewildering sense of frontier isolation for many residents.

Some Nashville residents compared the frequent, vivid failure of powerlines and transformers to a fireworks show. Others likened the accumulation of snow and ice on streets, blown and drifted by bitter northerly winds, to frozen ocean waves. One man, taking a break from storm clean-up, warmed himself by a portable indoor heater, only to walk back outside and see the buttons on his overcoat shatter due to the sudden freeze. The storm cost 25 lives and caused 500 more injuries. The final price tag of $100 million, or nearly $1 billion in 2017 dollars.

Fortunately, in 1951 many homes still possessed alternative means of heating like wood stoves and fireplaces. Likewise the dependence on communications and transportation was much less then compared to now. How much more disruptive might a storm of the same magnitude be today?