Record-threatening high temperatures have made headlines all summer across much of the US, driving many to seek relief poolside or at their favorite beach or lake. However, for some the heat wave means much more than eye-opening numbers on their electric bills. Just where and when can farmers and others whose livelihoods depend on routine wet weather expect alleviation of the drought?

High temperature records have been falling all across the East in the past few weeks. Columbia, SC has seen highs of at least 98° F for 20 of 27 days in July (normal highs there are closer to 93° F). Rainfall in Columbia for the month of July is running only about 38% of normal. Indeed, significant yearly rainfall deficits are common across much of the East:

- Columbia, SC: -7.81”

- Buffalo, NY: -7.08”

- Boston, MA: -6.43”

- Newark, NJ: -6.04”

- Atlanta, GA: -6.03”

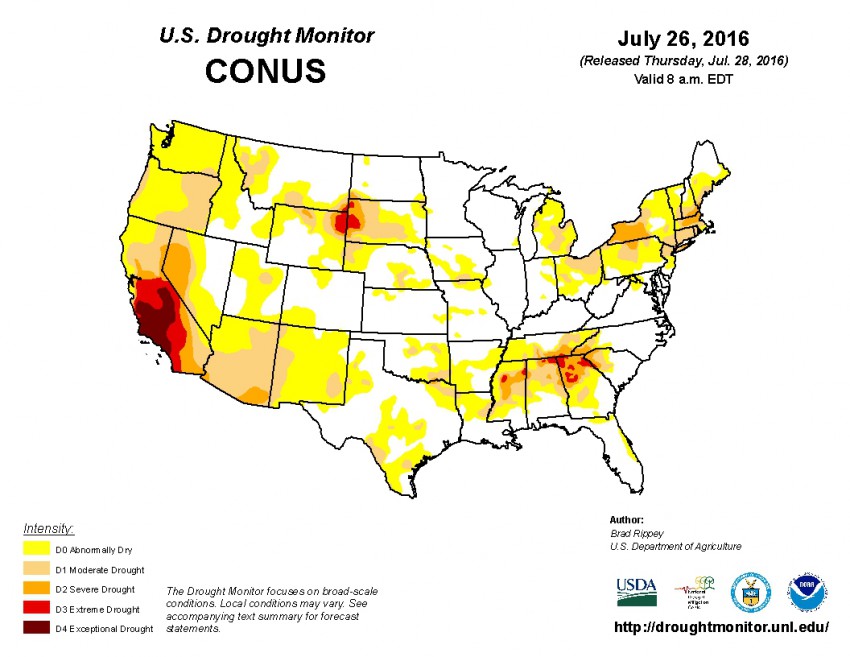

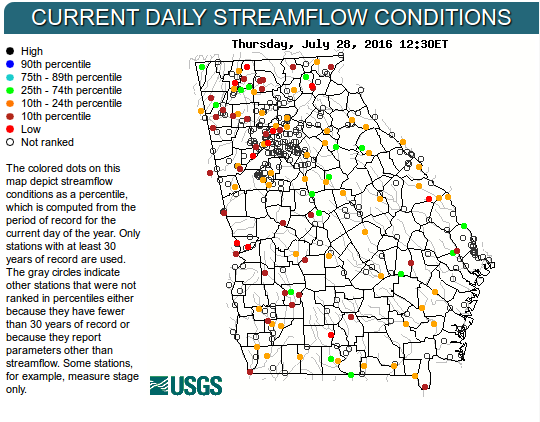

The combination of precipitation deficits and chronic heat is quickly leading to serious drought conditions, most acutely in parts of the interior Southeast and Northeast, in addition to the long-lived extreme drought that continues to grip the Southwest (see image at top). Topsoil moisture is very low across much of the Northeast and the Southern tier (fig 2 below). In Rhode Island, for instance, 97% of the state is reporting short to very short of normal topsoil moisture amounts. The rainfall deficits are starting to affect river and lake levels as well (see fig 3). Reduced topsoil moisture levels and standing water sources are starting to affect crop harvest prospects. In New York, the USDA notes that corn yields are expected to be low and that soybeans are in bloom and starting to show signs of distress. The wheat harvest in the Dakotas is likewise expected to be significantly hindered.

Unfortunately farmers can’t look to the current climate pattern for much comfort, especially across the South. Sea surface temperatures over the equatorial Pacific continue to indicate a shift towards a mild La Niña, confirming forecasts by most of the model guidance (see fig 4 below). Chances for La Niña development this winter are running up to 60%, compared to 40% for ENSO-neutral conditions and less than 5% for El Niño (see fig 5). La Niña winters are typically associated with drier-than-normal conditions across the southern tier of the US, although the picture is more optimistic over the central and north. Atlantic hurricane activity typically increases in a La Niña pattern, leading to a somewhat greater chance that a tropical cyclone could produce an organized heavy rain episode. However, even under the best of circumstances, tropical cyclone induced rainfall occurs over a rather limited area for a short duration, leading to serious flooding but not always efficient absorption of water into the soil. Widespread drought alleviation from one such system is unlikely.

The outlook for the next three months calls for above normal temperatures to continue nationwide (fig 6 below), with near to below normal precipitation for all but the Northern Plains (fig 7). The persistent warm, dry conditions will put pressure on agricultural interests heading into the prime harvesting season. Firefighters will likewise continue to face an elevated wildfire threat.