During the spring of 1816, many across North America and Europe observed a mysterious “dry fog” that stubbornly resisted the efforts of rain, wind or sun to disperse it. This fog dimmed the sun enough so that sunspots were visible to the naked eye, and led to brilliantly colored sunsets such as the one captured by painter J.M.W. Turner in his Chichester Canal (see image above). However, as the spring turned to summer and temperatures refused to warm, what had been a curiosity became a crop-killing disaster. Hard freezes periodically affected the northeastern U.S. and parts of Europe throughout the summer months, leading to failed harvests and skyrocketing food prices in what historian John D. Post described as the “last great subsistence crisis of the Western world.”

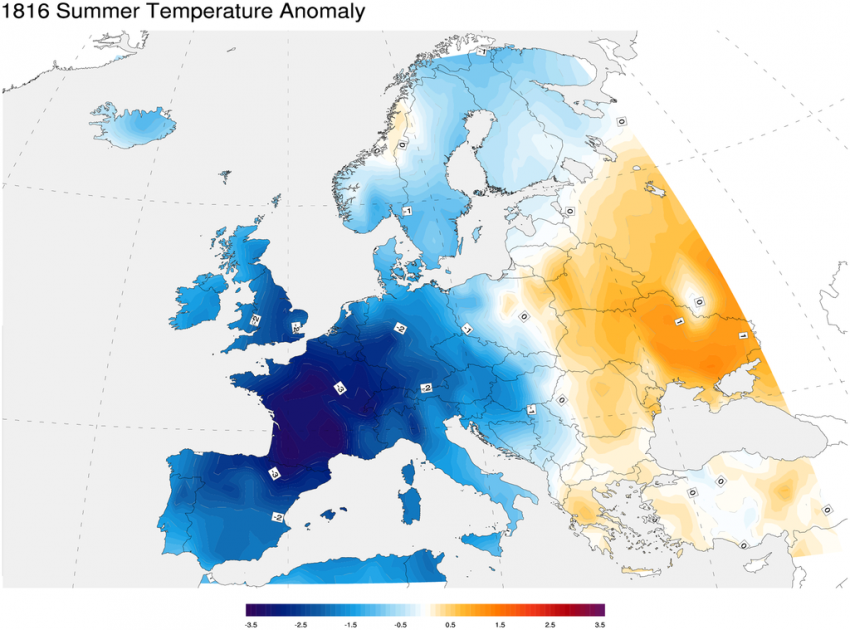

The root cause of this aborted summer could hardly have been guessed at even by scientists in the early 19th century, although only a few decades earlier no less a world-famous thinker than Ben Franklin had speculated correctly about the connection between significant global-scale cooling and the 1783 eruption of the Icelandic volcano Laki. But in early April 1815, Mount Tambora had erupted spectacularly in what is now Indonesia, the largest volcanic explosion of the millennium, propelling an ash plume as high as 43 km (27 miles) up into the atmosphere. This massive ash cloud entirely obscured the sun for three days within 600 km (370 miles) of the volcano, and within months enshrouded much of the rest of the globe. Perhaps as much as 100 million metric tons of sulfur dioxide were released into the atmosphere, reacting with oxygen there to produce a dusty haze of sulfuric acid. This aerosol veil significantly reduced the amount of solar radiation able to reach and heat the ground, causing temperatures to drop from one to as much as 3° C over New England and parts of Europe (see image below).

While it might not sound like much, this cooling of just a few degrees caused what must have seemed like completely upside-down weather. Morning ice crusted lakes and ponds as far south as Pennsylvania during the summer of 1816. A “winter” storm in early June caused snowflakes to fly in Albany, New York, with up to a foot of snow accumulation affecting Quebec City in southeastern Canada. Across the Atlantic, widespread crop failures and resultant famine contributed to a devastating three-year typhus epidemic in Ireland. Ash contamination led to reports of red and brown snow during the summer in Hungary and Italy. Food riots gripped the United Kingdom and France, while the Swiss government was forced to declare a national emergency. The monsoon season in India and China was severely disrupted, leading to see-sawing periods of drought and torrential flooding.

This frigid summer of 1816 occurred near the end of the climatic era known as the “Little Ice Age” that spanned several centuries and was characterized by lower than normal temperatures and greater snowfall, shorter growing seasons, and a greater extent of glacial ice coverage worldwide. Global temperatures have generally risen from the latter part of the 19th through the 20th and 21st centuries. Advances in farming and transportation technology have also helped mitigate the once-devastating impacts of sudden climate disruptions like the one caused by the Mt. Tambora eruption. However, it remains the case, especially in developing countries, that food production is highly dependent on predictable seasonal weather patterns. Disruption of these patterns, whether by abrupt events like volcanic eruptions or by longer-term shifts in climate, can still lead to devastating famines.