The historic El Nino that has been impacting weather patterns around the world since mid-2015 appears to be in its final stages. Satellites and sensors are showing the unusually warm waters in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean that make up El Nino are cooling, and the majority of computer models suggest a return to neutral conditions by June.

But the departing El Nino certainly left its mark. Depending on what metric is used, this El Nino will go down as the strongest on record, or at least tied with the El Nino of 1997-98 for the strongest since records began being kept in 1950. And the impacts to weather in the U.S. were profound. There were severe weather outbreaks in the Southeast, flooding rains in Texas and Louisiana, unusual wintertime warmth for the Great Lakes and Northeast, and an usually quiet Atlantic hurricane season, all of which can be tied to El Nino.

There was also optimism that this El Nino would help alleviate the drought in California, the worst to affect the state in 500 years. The cautious optimism was rooted in prior El Ninos, which tended to cause above average precipitation during the winter months in the Golden State. And as expected, the current El Nino did help steer more storms into the western U.S. this winter, producing above average precipitation. However, the overall results in California are mixed.

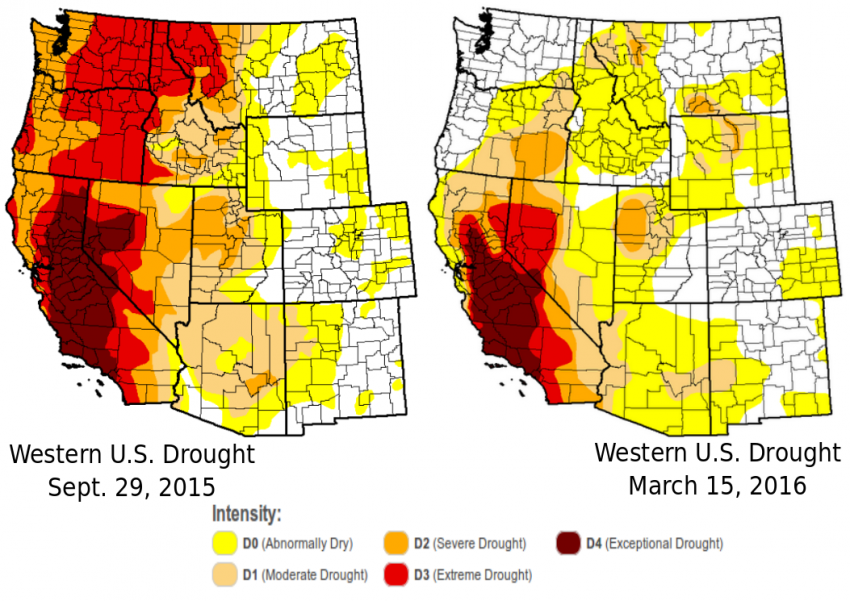

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, California did see reductions in drought, with the three most severe classification categories–Severe, Extreme and Exceptional Drought–each declining between 10 and 20 percent since October. However, since many of the wintertime Pacific storms that rolled in took a northerly track, the most dramatic reductions in drought occurred in places such as Washington, Oregon, Idaho and western Montana. As for California, despite some improvement, around 35 percent of the state still remains in Exceptional Drought, the worst category, including much of the state’s agriculture dependent Central Valley.

Another key measurement is the amount of snowpack in California’s Sierra Nevada range, as the melting snow is critical for refilling reservoirs that the state’s 38 million residents rely on for drinking water. As of March 18, the snow water equivalent in California’s northern Sierra was at average levels; 91 percent of average in the central Sierras; and 76 percent of average in the southern Sierras. The numbers are good, but not great, according to the California Department of Water Resources (DWR), which says it would have taken 150 percent of average wintertime precipitation and snowpack to ‘significantly ease’ the critical shortage of water. While the total snow wasn’t as much as officials were hoping would fall, the current snowpack is dramatically higher compared to last winter. At the end of March 2015, snowpack levels were only 5 percent of average levels, the lowest ever recorded.

So despite the extra precipitation this winter, the critical shortage of water remains. The DWR estimates they will only be able to provide 15 percent of the total water requested by municipalities and contractors this year.

It would take several more winters similar to this one to end California’s drought, now entering its fifth year. However, an El Nino pattern is not expected to return next winter, and could instead be replaced by El Nino’s counterpart: La Nina. While La Ninas’ impacts are not as pronounced on the state as El Ninos’, they sometimes lead to below average precipitation in southern California. So those in the parched state will have to hope other factors will override that trend, and bring the return of the rains and snows next winter.