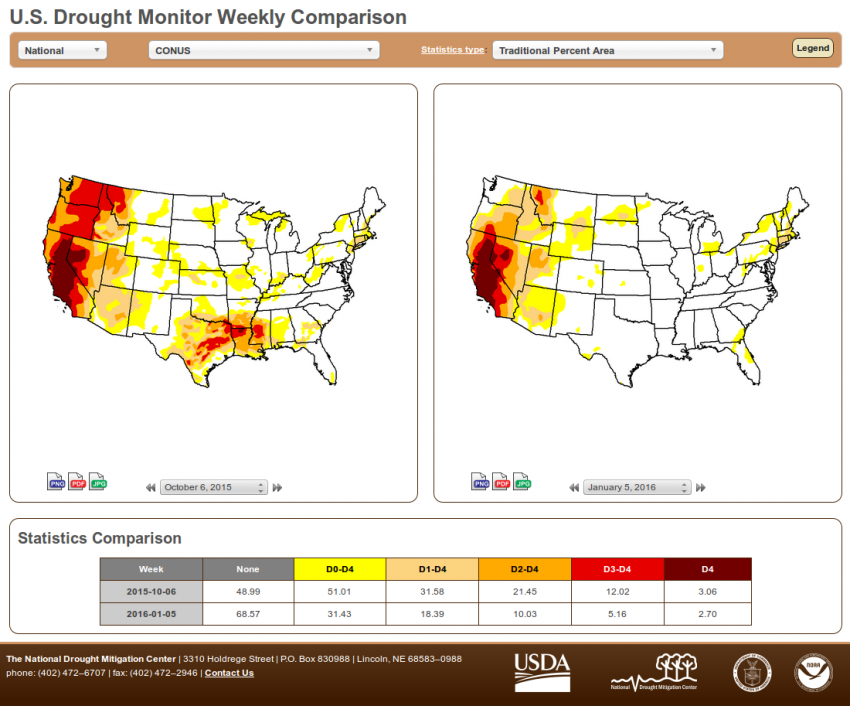

Since October, much of the Pacific Northwest and Mid-South has seen significant improvement in the drought that had been plaguing those areas earlier in the year. In some cases, locations that were in the “Extreme” or even “Exceptional” drought category have improved all the way out of official drought status entirely (see figure one comparing drought conditions in early October with the current analysis courtesy of the U.S. Drought Monitor). Similar relief may be on the way thanks to a favorable El Niño pattern for areas of California and western Nevada that have been parched for two years.

The areas that have seen alleviation from the drought can thank above- to, in some places, well above-average precipitation that has fallen over the past few months (see figure two, precipitation anomalies over the past 90 days recorded by the Climate Prediction Center). The cost of drought improvement in some places has been destructive flash or river flooding, but in the grand scale and in the long run, drought alleviation

will prove beneficial. This kind of storminess and above-normal precipitation in the West and South matches forecasts based on strong El Niños, such as the one we’re experiencing now, which tend to lead to a more active subtropical jet stream transporting abundant Pacific moisture into the United States. Sea surface temperatures over the tropical Pacific remain several degrees above normal over a vast area of the ocean, as indicated by the unexpected development of Hurricane Pali, the earliest hurricane ever to form in the Central Pacific. Pali will threaten land masses with little more than somewhat elevated surf, but it’s an impressive sign of El Niño’s influence.

Evidence suggests that the current El Niño has just passed its peak intensity but is likely to remain in the warm phase through the next several months, meaning opportunities for additional drought alleviation in California. One or two hard-hitting if short-lived storms have made headlines recently after causing significant flooding in some of the prominent West Coast cities, but much of central and southern California remains in the “Exceptional” (most severe) category of drought, a calamity going on two years in duration that has decimated the water supply and led to severe restrictions on water use. However, the storm track that has thus far favored the Pacific Northwest is expected to shift further south over the next few weeks (see CPC precipitation outlooks in figure three, for week two, and figure four, for weeks 3-4), potentially targeting the most drought-stricken portions of California. A succession of winter storms could produce not only much-needed rainfall over the valleys but heavy snows in the Sierra Nevada range, fortifying the snowpack that’s already running near normal, a far cry from last season when many snow-starved resorts simply couldn’t open. If this snowy pattern unfolds as expected it’ll be to the delight of not only skiers and snowboarders now but also farmers in the valleys below that depend on abundant snowmelt water for the growing season that begins as the ski season is coming to an end.