We’re all familiar with rivers of water on Earth’s surface, but rivers of a different kind also exist in the sky. Atmospheric rivers are flows of airborne moisture that are thousands of miles long and hundreds of miles wide. Each of these moisture flows can transport more water at any given time than the entire Amazon river, the largest river on Earth.

One of the best known atmospheric rivers has been given its own name: Pineapple Express. A Pineapple Express typically occurs in the winter when the polar jet stream over the Pacific Ocean dives south from Alaska, forming an atmospheric river from the western Pacific to the west coast of North America that tends to bring lots of rain to the low country and snow to the mountains of the Pacific Northwest and California. While the phenomenon itself is not particularly rare, the pattern has been known to occasionally produce extreme amounts of precipitation in the western United States.

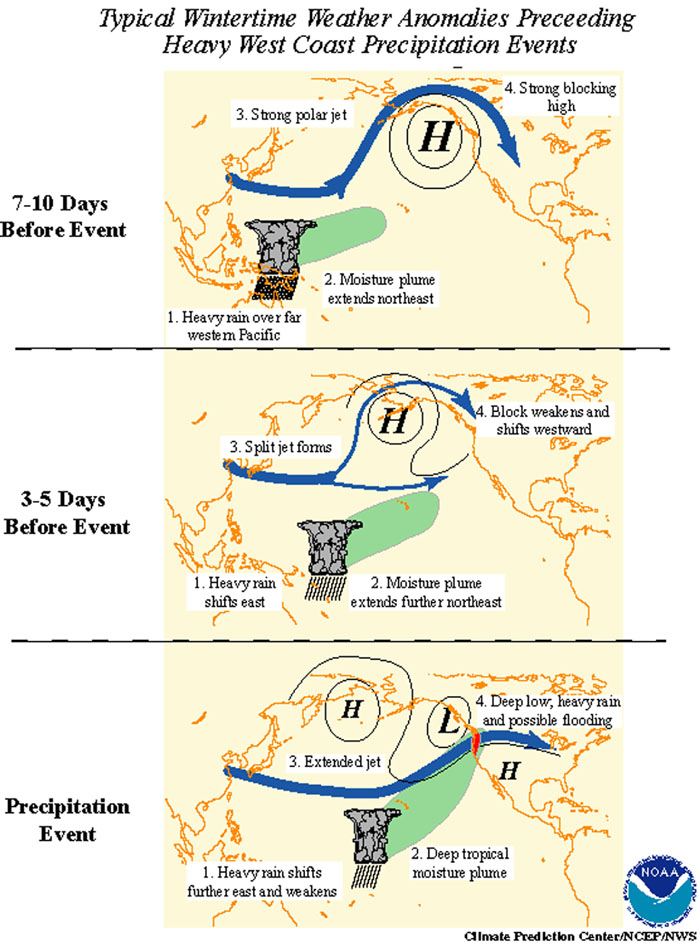

About a week before a Pineapple Express begins, heavy rain will be noted within a broad area of moisture over far southeastern Asia. At the same time, the polar jet stream will be oriented in a southwest to northeast direction as it moves into North America (typically over Alaska), with a ridge of high pressure off the coast of British Columbia. The area of moisture over Asia will then start to migrate to the northeast, into the open Pacific.

Diagram by NOAA showing the evolution of what is commonly referred to as the ‘Pineapple Express’

Diagram by NOAA showing the evolution of what is commonly referred to as the ‘Pineapple Express’

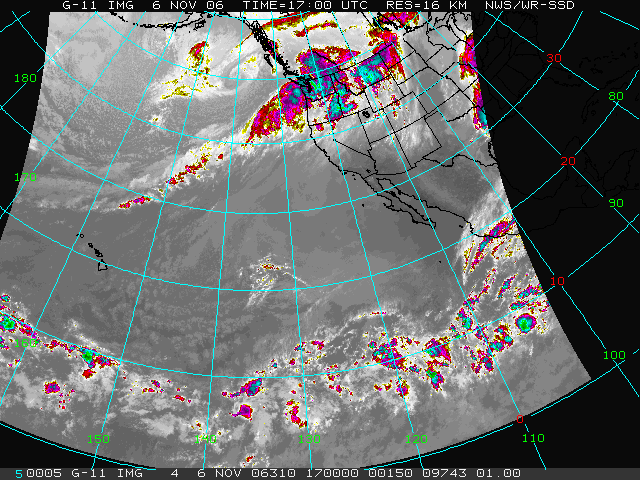

Around 3-5 days before a Pineapple Express, the polar jet will split over the central Pacific, with the northerly portion weakening as the southerly branch dives south towards California. The Pineapples Express officially gets underway as the southerly jet gains strength, forming a low pressure system off the coast of Canada and the Pacific Northwest. The low pressure helps steer the advancing plume of moisture from the Pacific Ocean into North America, usually producing several days of rain and snow. The satellite image at the top from NOAA shows a strong event in 2006, with the clouds of the Pineapple Express stretching from Hawaii to Washington, bringing heavy rain to the West Coast.

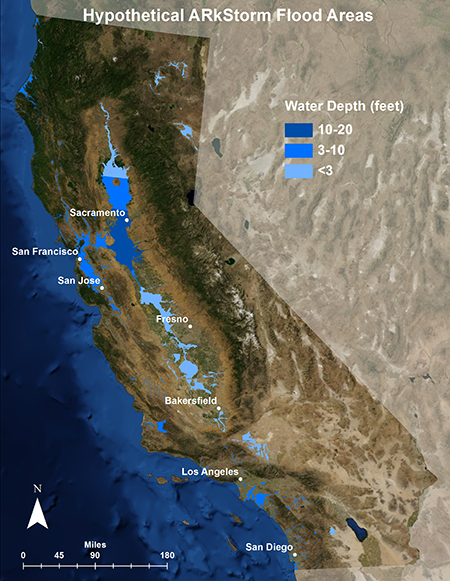

One particularly extreme event was the Great Flood of 1862. For more than six consecutive weeks, storm after storm slammed Oregon, Nevada, and California – each storm tapping into a river of water vapor streaming in from the Pacific. The city of Sacramento was hammered with a combination of massive rain totals as well as warm air at high elevations melting large quantities of snow. The double whammy of water being poured into the rivers inundated the city and entire Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys with several feet of water.

Of course this is rare, with such an extreme situation statistically occurring once every couple hundred years. Nonetheless, the threat for the future is very real. As such, the US Geological Survey created a fictional, though realistic, simulation in which the event was called ARkSTORM. The conclusions drawn were astonishing. Based on the simulation, damage from the ARkSTORM could reach $725 billion, which is three times higher than estimated damages caused by “the big one” earthquake. The simulation found a quarter of all buildings in California would be damaged by flooding, and insurance costs would be permanently pushed higher. Luckily, unlike earthquakes, this type of event can be reasonably predicted over a week in advance. Weather models keep getting more powerful and forecasts of extreme events are improving. Whether it’s an ordinary Pineapple Express or the next Great Storm, it will not be a complete surprise.