People who live in such different locales as New Orleans, Louisiana, Chicago, Illinois, and Banda Aceh, Indonesia have at some point faced massive, deadly swells of water. In a crisis mode they may not have known or cared to know about the technical term or cause of their imminent destruction. However, the three superficially similar phenomena that devastated those communities originated from completely different causes with different implications for predictability.

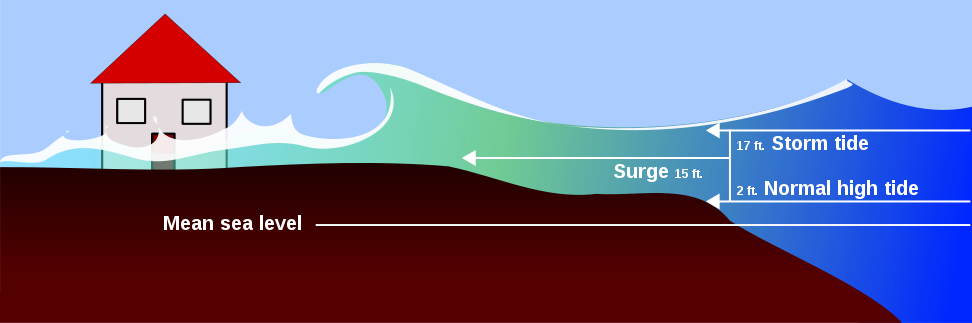

While many focus on the high winds caused by hurricanes, it’s actually the storm surge, the swell of water pushed onshore by the strong wind flow around the circulation (see figure below), that represents the greatest threat to life and property. The size and strength of the cyclone, the shape of the coastline and nearshore sea floor, and the speed of the storm are all factors that determine the height of the storm surge. Portions of coastal Mississippi saw storm surges with Hurricane Katrina of at least 10-12 m (34-39 feet), despite the fact that Katrina had weakened significantly from its peak intensity over the open Gulf of Mexico. Fortunately the latest storm surge computer models incorporate detailed topography to make very accurate forecasts about localized fluctuations in surge height, crucially important information for evacuation planners.

A seiche (pronounced “saysh”) is much like a storm surge, except that it occurs in closed or nearly closed bodies of water such as lakes or bays. They can be caused by strong winds or by a nearby earthquake. The effects are obvious on smaller bodies of water like ponds or even backyard swimming pools as a “slosh” of water rebounding visibly from end to end. Seiches are almost always present on larger bodies of water like the Great Lakes, usually without us even being able to perceive them. In fact engineers plan for routine seiche surges when building everything from dams to spent nuclear fuel containment vessels. Large, damaging seiches are rare, but dangerous when they occur. A three meter (nine foot) seiche wave struck the waterfront of Chicago, Illinois seemingly out of nowhere on a hot afternoon in June 1954, sweeping eight fishermen to their deaths. It had been caused by a squall line of thunderstorms pushing water to the opposite shore, which then sloshed back to the Chicago side several hours later.

The last type of destructive swell is the tsunami, caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, often by an undersea earthquake. The tsunami is almost imperceptible over the open ocean (one meter or less in height), but it moves at tremendous speeds (up to 500 mph, or 800 kph). As the tsunami waves approach shallower waters near shore, they pile together like fabric bunching up against a sewing machine’s needle, slowing down but quickly gaining in height and destructive power. An earthquake that occurs near the coast can provide a warning for those in immediate danger, allowing for an evacuation to higher ground. However, tsunamis moving across ocean basins can seem to come totally “out of the blue”. Recall home videos of vacationers blissfully enjoying the sun and surf at resorts in Thailand, bewildered by the sudden withdrawal of the ocean and the terrifying waves that followed. The last 80 years have seen concerted international efforts to create a tsunami warning system composed of seismic sensors, wave-monitoring buoys, and an effective alert transmission apparatus. This kind of system was largely absent from areas affected by the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, but probably saved millions of lives when a tsunami of similar magnitude struck the east coast of Japan in March 2011.