Residents of the British Isles can be forgiven for coveting the warm, sunny summers enjoyed by Americans across much of the contiguous US. Nobody’s going to mistake the many parts of the U.K. that remain locked in a cool and blustery pattern for weeks at a time in the summer for tropical getaways, but the fact is they could have it worse, especially in the winter.

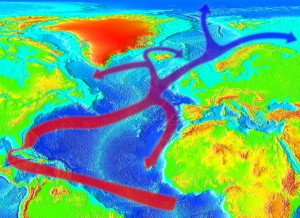

London lies near 51.5° N latitude, farther north than any point in the lower 48 United States, at around the same latitude as St. Anthony on the northern tip of Newfoundland, Canada. St. Anthony perennially endures a long, brutal winter season, averaging more than 198 inches (500 cm) of total snowfall with high temperatures in February normally around 18° F (-7.7° C). By contrast, Londoners enjoy relatively balmy highs around 47° F (8.1° C) in February with seasonal snowfall totals averaging less than 18 inches (50 cm). The difference can be explained to a degree by the moderating influence that sprawling urban London has on temperatures, but the more important factor is the Gulf Stream, the river of warm water that flows from the Gulf of Mexico up the Southeast U.S. coast and across the Atlantic Ocean to western Europe and the British Isles (see image below).

Warm Gulf Stream waters combined with westerly winds aloft can provide a favorable channel connecting the tropical waters of the Atlantic basin with Europe, and once or twice every season a tropical cyclone successfully makes the trip. In 1998, Hurricane Mitch, one of the deadliest storms ever recorded in the tropical Atlantic with almost 20,000 fatalities to its name, traversed the Atlantic after devastating portions of Central America to expend the last of its fury on Ireland, producing wind gusts to 90 mph (140 kph) and waves to 30 feet (9 m) on the Irish coast.

The cross-ocean connection isn’t limited to the warm season. Forecasters on both sides of the Atlantic pay close attention during the winter months to the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), a variation in the position and strength of semi-permanent high and low pressure centers in the central and northern Atlantic, respectively. The negative phase of this oscillation, when both pressure centers weaken, allows cold Arctic air to more easily intrude south, often setting the stage for severe winter storms. The notorious winter of 2009-10 was characterized by crippling snowstorms and prolonged Arctic outbreaks on both sides of the Atlantic due to the combination of a persistently negative NAO with a warm phase ENSO (aka El Nino).

The Pacific Ocean also sees systems periodically bridge the vast divide between Asia and North America. In early November 2014, Typhoon Nuri spun up just east of the northern Philippine Islands, rapidly intensifying to Category 5 status within 72 hours and becoming the third-strongest cyclone globally in 2014. Fortunately the storm moved over open waters for the duration of its tropical lifespan, and by 6-Nov it was moving quickly north over cooler water, transitioning to an extratropical storm. Unusually strong upper level winds, however, allowed it to retain its intensity, eventually becoming the strongest Bering Sea storm on record. The storm dislodged a chunk of frigid Arctic air and sent it plunging south into the U.S. New low temperature records were set in cities across the Central and Eastern US, and lake effect bands dumped several feet of snow downwind of the Great Lakes between 17-19 November. It’s a rare and impressive sight to see a warm tropical cyclone indirectly catalyze an Arctic outbreak and prodigious snowfall more than 6,000 miles (10,000 km) away.