Many centuries ago, the Incas of Pacific coastal South America had a keen and immediate awareness of the impacts of a strong El Nino. Evidence suggests they resorted to mass human sacrifices to appease the gods of the Sun and Moon they felt were punishing them with cataclysmic rains and flooding. But radiocarbon dating of sea shells along the coast of Peru points to even earlier examples of El Nino, probably as far back as the end of the last Ice Age some 10,000 years ago.

However, El Nino was only officially referenced by name first in an 1892 report to the Geographical Society Congress concerning the unusual current of warm water observed by Peruvian fishermen that periodically devastated the local economy. As came to be known, abnormally warm water reduces upwelling of rich nutrients that form the bottom of the regional food chain, resulting in fish kills or unusual migration patterns. The fishermen reported that the effects were typically maximized around Christmas, hence the local name “El Nino”, Spanish for “Christ Child”. The threat has persisted through today, especially as the frequency and duration of strong El Nino events may be on the increase due to global warming.

A few years after the term “El Nino” was first given the stamp of scientific authority, a British mathematician named George Walker, stationed in India to study the famous monsoon there, observed a distinct tug-of-war in atmospheric pressure readings between the Eastern and Western Pacific that he coined the Southern Oscillation and that appeared to have major implications for weather patterns across the globe. But it wasn’t until Norwegian-American meteorologist Jacob Bjerknes used data accumulated during the 1957 International Geophysical Year research project to link the oceanic and atmospheric components of what came to be known as ENSO (El Nino-Southern Oscillation). Bjerknes and his colleagues not only described the empirical connection between the two phenomena but the underlying physical explanation as well, recognizing the impact that ENSO had on trade winds, the currents of air that move major weather systems and determine large-scale, long-term patterns of precipitation like monsoons.

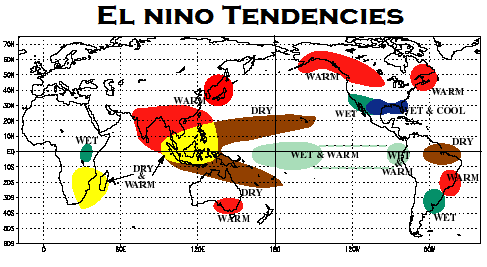

Interest spiked in the ENSO, especially the warm phase still known as El Nino, during the winter of 1982-83, the strongest amplitude warming event of the century up to that point. Record-shattering rainfall led to severe flooding in Ecuador and Peru as well as western and southern portions of the US, while parts of Australia, Indonesia, and interior South America suffered from devastating droughts and wildfires. The Peruvian fishing economy was crippled by an almost total failure of the anchovy harvest and the bewildering migration of sardines to cooler waters further south. The event came as a surprise to the atmospheric scientific community at large and instigated numerous research projects as well as the installation of dozens of new sensor packages across the Pacific to monitor variables like sea surface temperatures. The result was a much more timely and confident forecast of the equally strong El Nino event of winter 1997-98.

This winter’s El Nino is well on its way to rivaling the events of 1997-98 and 1982-83 in terms of magnitude. For some it will bring a welcome relief from years of below-normal precipitation, but others, like the Incas, dread the potential for a season of stormy mayhem.