Every Fall, the clash of the first surges of cold air from Canada with lingering warm air from the southern U.S. leads to rapidly intensifying storms accompanied by high winds and churning seas over the Great Lakes, with deadly consequences for ships unfortunate enough to be caught over the open water. These hurricane-strength gales have become known as “November Witches”.

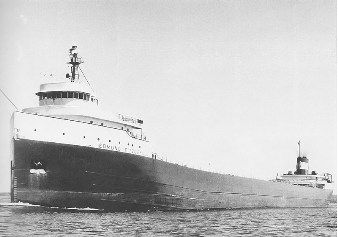

Probably the most famous victim of the November Witch is the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald (figure one) on Lake Superior. On November 10th, 1975, a fierce low pressure system started to develop over the Great Lakes, with the initial NWS forecast tracking the storm just to the south of Lake Superior. The Fitzgerald plotted a course along the north shore of the lake to avoid the worst effects, however the storm tracked farther north than predicted, catching the Fitzgerald off guard. From the early hours of the day through the early afternoon, rough conditions, though not unusually rough, hounded the ship. Around 2 p.m. the storm’s center passed almost directly over the ship, and the wind direction changed to northwesterly. By 3 p.m. winds were approaching gale force, and reached as high as 67 mph into the early evening. The high winds allowed the wave heights to easily exceed 20 feet. While there are many contending theories for what actually sank the Fitzgerald, rogue waves are considered one of the most likely.

Shortly after 7 p.m., another ship in the area, the Arthur M. Anderson, logged rogue waves as high as 35 feet, heading in the direction of the Fitzgerald. The last communication from the Fitzgerald came at 7:10 p.m., and by 7:20 p.m. the ship was lost to all radio and radar contact. All 29 of the ship’s crew perished.

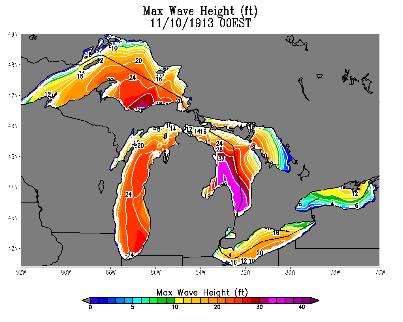

While the storm that sank the Fitzgerald has gone down in folklore (thanks largely to the chart-topping Gordon Lightfoot song), the most destructive and costly November Witch occurred in 1913 – more infamously known as “the White Hurricane”. A strong low pressure system moved towards the Great Lakes from the northwest on November 6th and 7th, bringing hurricane force winds to portions of Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron into the morning of the 9th. While intense, the storm weakened as it moved east, leading to a common assumption that the storm was just another strong November gale and all was winding back to normal. Unknown to many ships that were already sailing, another low pressure system, not analyzed on the crude weather maps of the day, was forming quickly over the mid-Atlantic. The two systems merged and rapidly intensified over Lake Erie and southern Lake Huron, a meteorological “bomb”, the term used to describe storms whose pressure deepens 24 millibars in less than 24 hours. The result was an unexpected and drastic increase in winds, sustained at hurricane force on Lake Huron. With wind direction from the northwest, the wind speeds were unmediated by friction from land and created huge swells on southern and western Lake Huron, as shown by the NOAA wave height graphic (figure two). Twelve ships (including 8 on Lake Huron) were sunk in the huge waves with the loss of over 250 people. Of the 12 ships, 4 have never been located.

Fig. 3: Waves crash ashore from Lake Michigan during the 1913 storm, dwarfing the onlooker