For two years we’ve seen startling pictures out of California of once-robust lakes and rivers reduced to trickles through desiccated landscapes and satellite images showing the Sierra Nevada Mountains almost devoid of snow cover in the heart of the winter. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been diverted from federal, state, and municipal funds to help prop up what was already a notoriously fragile economy, highly dependent on those aspects like agriculture and tourism that have been hardest hit by the drought. Water management plans were devised based on the fundamentally misleading precipitation rates and water levels of an abnormally wet 20th century, probably the wettest of last millennium judging by tree ring climate data. Population surges in prone areas and the resultant diversion of finite water resources coupled with rising global temperatures have helped turn what might otherwise be a natural restoration of climatic normalcy into a calamity.

For the fourth straight month residents of California exceeded Governor Jerry Brown’s goal of a 25% reduction in water usage in September. Brown announced the mandate in April, a hard-edged response to the drought to be enforced by a variety of financial penalties for exceeding the allowance. The achievements of Californians in water conservation have been laudable, but unless the drought weakens these arduous restrictions will have to be continued through early 2016.

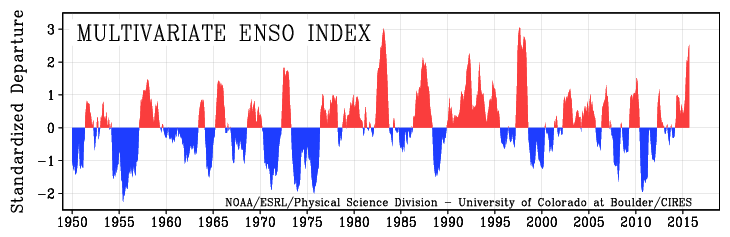

A historically strong warm phase of the ENSO, popularly known as El Nino, may hold the answer to many fervent prayers for weather patterns to change for the wetter. The Multivariate ENSO Index (MEI) used to gauge the strength of the ENSO shows (see figure below) a departure from normal of nearly 2.5, the highest level since the winters of 1997-98 and 1982-83, a value that’s still climbing. In addition, the MEI values are climbing at a rate and time of year quite in line with those previous events. Those two winter seasons ultimately proved to be among the wettest on record in the West and South. The winter of 1997-98 was statistically the 5th-wettest ever measured in California, including a February that was the wettest in the 100+ year official record. Downtown Los Angeles saw 13.68″ of rain in February 1998, 92% of the amount they usually expect to see in a full calendar year. In all, nineteen weather observing stations in California broke monthly precipitation records for February. A similar stormy pattern in the winter of 2015-16 would go a long way towards recovering the precipitation deficit caused by 2+ years of abnormal dryness.

However, it is important to note that not all El Nino events are accompanied by record-breaking (or even above normal) precipitation, although the strength of this event lends credence to the idea that Californians will enjoy a wetter pattern.

Additionally, a certain kind of wet winter won’t necessarily “save” California. Too much water too fast will cause disruptive flooding, and will contribute to excessive runoff and river overflow rather than being efficiently absorbed into the system. Above normal temperatures will also tend to inhibit growth of the Sierra snowpack, a vital part of the normal water cycle for drought-stricken parts of the state. In looking forward to the prospective benefits of an El Nino winter, it’s important to recognize and prepare for the consequences of an abrupt end of drought.